Le Trésor d’Orphée, Paris 1600

In France, the wars of religion of the late 16th century took a heavy toll on lute music; as far as we know, none was published in that century after the year 1571, which saw Adrian Le Roy’s last known collection. Publications for the lute would only resume in 1600, with Anthoine Francisque’s Trésor d’Orphée, published in Paris.

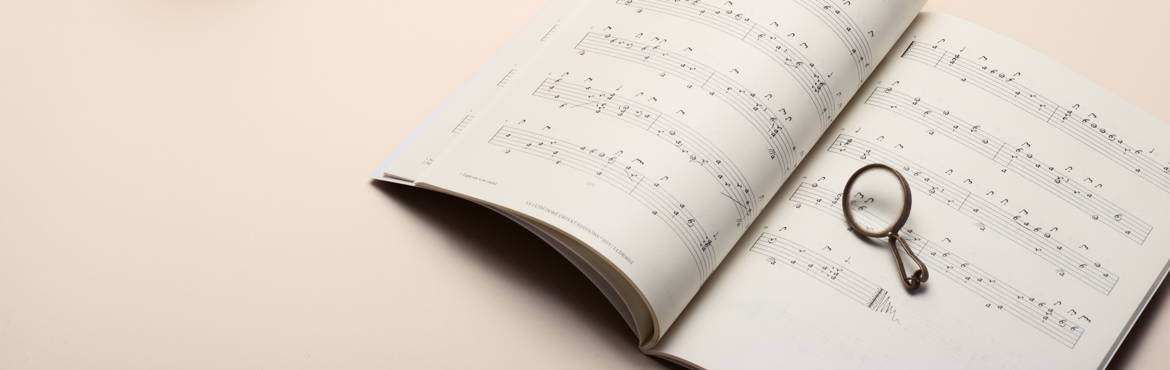

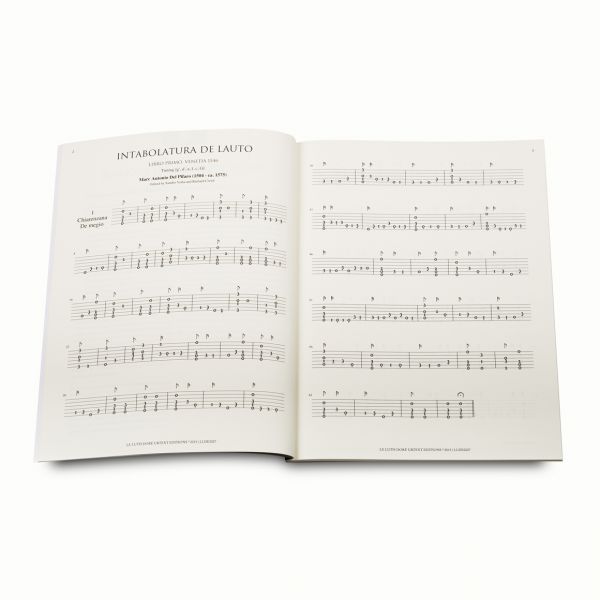

There is apparently only one extant copy of the work, kept at the National Library in Paris. Printed with great care by the publisher Ballard (formerly Le Roy & Ballard), with the same characters as those used thirty years earlier for Adrian Le Roy’s book of Airs de cour (1571), to collection contains 71 pieces: two adaptations of vocal polyphonies, seven free compositions (fantasies, preludes) and 62 dances.

The work’s overall structure, with its mixture of polyphonies, free compositions and dances, is not unlike the content of tablatures published during the 16th century. However, two pieces, which fall into the category of “adaptations”, are particularly atypical. Francisque’s version of Roland de Lassus’s Suzanne un jour, a very well-known and highly appreciated song at the time, with countless instrumental adaptations, is all but unrecognizable.

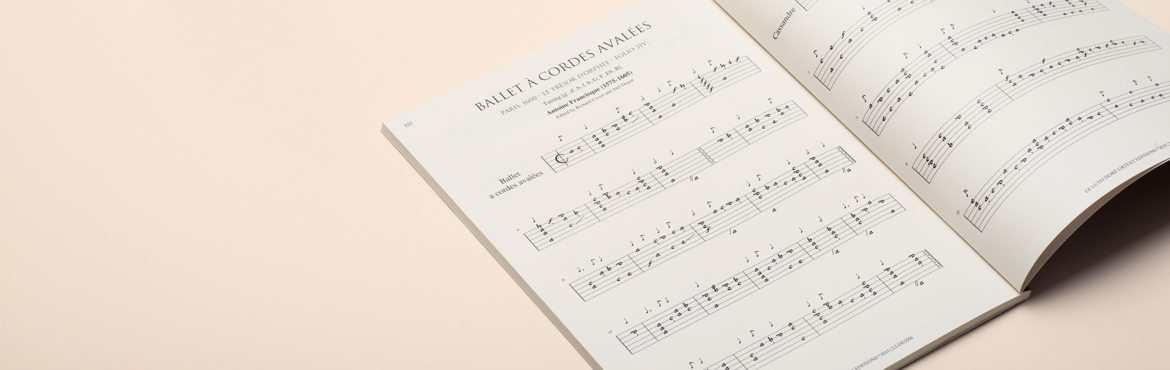

As for the Cassandre that concludes the collection, it is not strictly speaking a vocal polyphony, since its origin seems to lie in a Branle coupé nommé Cassandre as it appears in the famous dance treatise Orchésographie published by T. Arbeau in 1588.

An analysis of the two fantasies and five preludes reveals the transitional nature of Francisque’s compositional style, at a time when the fantaisie, whilst retaining its contrapuntal foundations, was receding from the forefront it occupied in 16th-century lute music, and the prelude, by virtue of its harmonic characteristics, was beginning to be considered an appropriate tonal introduction to a suite of pieces, a form that would develop throughout the 17th century.

Antoine Francisque (1570-1605)

Anthoine (Antoine) Francisque was born ca. 1570/75 in Saint Quentin, in northern France. He reportedly went to live in Cambrai, where he married Marguerite Behour, an innkeeper’s daughter, in 1596. Nothing is known regarding his musical education. In the early 17th century, he moved to Paris, in the rue Sainte Geneviève (Parish of Saint Etienne du Mont).

He most probably helped compose and perform music for ballets de cour, spectacles combining instrumental music and dance that preceded the opera and were reserved for nobility. His professional designation was maître de luth, and he must have taught the instrument.

In 1600, he published the only collection of lute pieces in tablature that we know of, Le Trésor d’Orphée, whose title corresponds to a fashion that would soon be reflected in other works such as the Thesausus Harmonicus (or Trésor harmonique by Jean-Baptiste Besard, 1603) or the Secret des Muses (Nicolas Vallet, 1618) amongst others.

Only three archival documents mention his name, one in 1601 recording an act of mutual donation between childless spouses, another reporting the baptism of his godson Antoine Rebans, the son of a contemporary lutenist, in 1605. The last one informs us of Francisque’s death in October 1605 in Paris, where he was buried in the Parish of Saint Séverin.

Joël Dugot | Le Luth Doré ©2015