My Store

The Haslemere Manuscript, Pieces and Lute Sonatas | Volume I

The Haslemere Manuscript, Pieces and Lute Sonatas | Volume I

SKU:LLDE0012

• Composer: Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687–1750)

• Title: The Haslemere Manuscript

• Subtitle: Pieces and Lute Sonatas

• Year of publication: c.1750–1780

• Source: GB-HAdolmetsch Ms II.B.2

• Volume: I

• Scholarly edition based on original sources

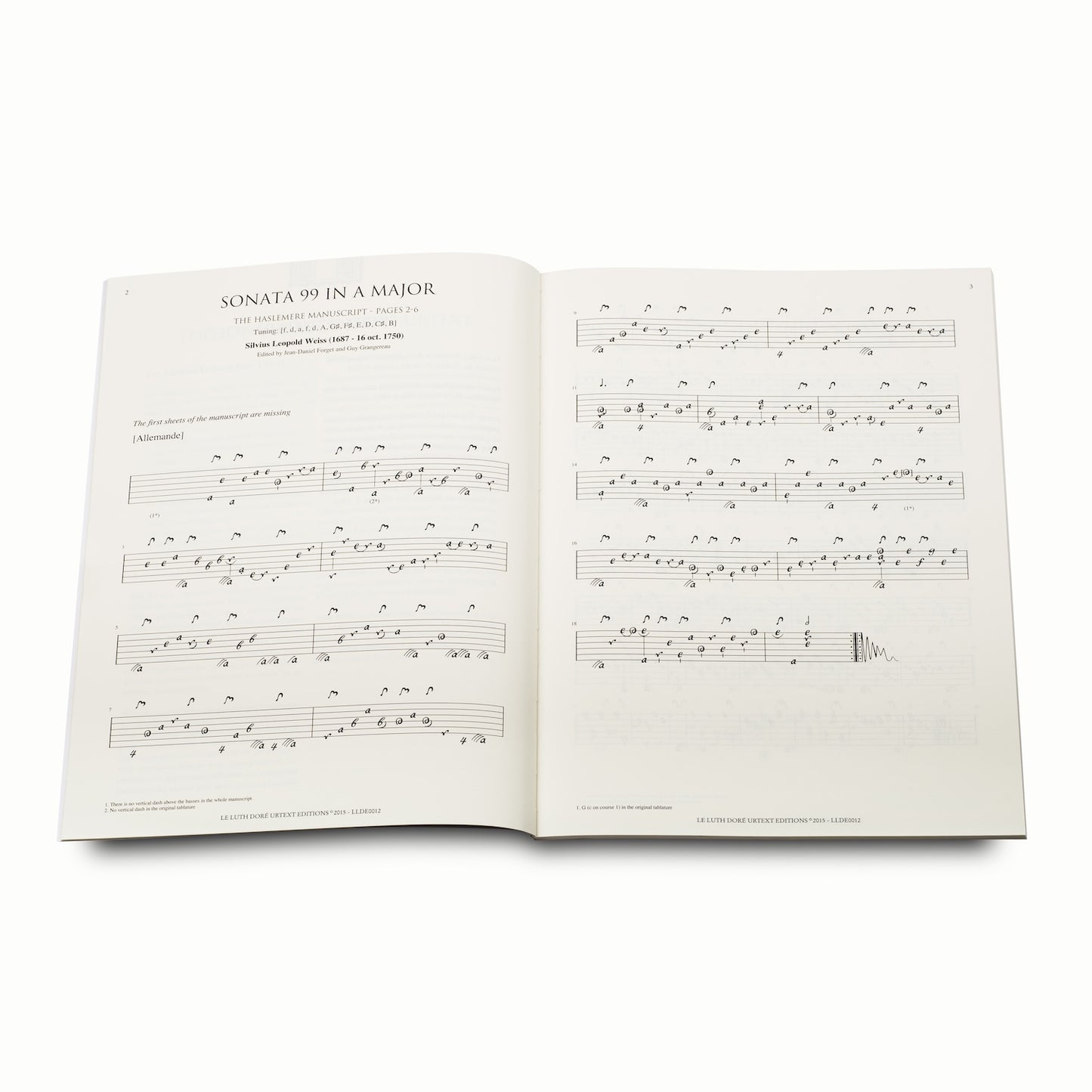

• Accurate transcriptions, historical fingering, optimal readability

• Ideal for concerts, research, or higher education

No VAT applied (Article 293 B of the French Tax Code).

Couldn't load pickup availability

Partager

Central European Resonances: Around Weiss

The first volume of a series drawn from the Haslemere Manuscript, this collection features several works for thirteen-course Baroque lute by Silvius Leopold Weiss, one of the greatest lute composers of the eighteenth century.

Copied in Dresden or Prague, these pieces reflect Weiss’s mature style and the evolution of lute writing at the crossroads of German and French traditions. Edition prepared by Jean-Daniel Forget and Guy Grangereau.

Product Details

Overview

The Haslemere Manuscript – Volume I: Works by Weiss

The Haslemere Manuscript, preserved in the Carl Dolmetsch Library in England, contains lute tablatures in D minor, most likely copied in the eighteenth century by a lutenist from Dresden or Prague. The pieces, often grouped by key, include anonymous or attributed works, without consistent indications of suites or sonatas. Acquired in the twentieth century by Arnold Dolmetsch, the manuscript reflects the development of the twelve- or thirteen-course lute in Central Europe.

Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687–1750)

Silvius Leopold Weiss, one of the greatest lutenists of the eighteenth century, composed exclusively for his instrument. Active in Dresden, he transformed the Baroque lute through the addition of a thirteenth course and a style of writing of exceptional harmonic richness. A close acquaintance of J. S. Bach, he represents the culmination of the galant style in the solo lute repertoire.

Editors

Jean-Daniel Forget – IT Specialist, Lutenist

Passionate about the Baroque repertoire, Jean-Daniel Forget is a self-taught lutenist who has been copying and disseminating early manuscripts for nearly twenty years. A computer professional by training, he is proficient in music notation software adapted for tablature. In collaboration with Guy Grangereau, he provides access to tablatures on a dedicated website. He also assisted Miguel Serdoura in the preparation of his editions and his Method for Baroque Lute.

Guy Grangereau – Guitarist, Lutenist

A professional musician, Guy Grangereau studied guitar in Paris with Turibio Santos before pursuing further training at the Martenot school. After teaching for twenty years, he now performs on a 16-course hybrid instrument and a theorboed Baroque lute. Since 2010, he has collaborated with Jean-Daniel Forget in copying and editing Baroque manuscripts, notably focusing on the works of Silvius Leopold Weiss.

Urtext Editions

Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions

Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions offer scores faithful to historical sources, optimized for musicians and musicologists. Our editions combine careful engraving, practical layout, durable materials, and a detailed critical apparatus in multiple languages.

Each text is rigorously established note by note to ensure an authentic restitution of the works, including original fingerings and ornamentations, as well as relevant stylistic suggestions.

Prepared by experts, our editions provide clear readability and informed interpretation of the early music repertoire.

We dedicate Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions to the memory of William H. Roberts († 2024), cofounder and source of inspiration for this collection. Without his vision and unwavering support, these editions would never have come into being.

Technical Details

• Editor(s): Jean-Daniel Forget & Guy Grangereau

• Musical period: Baroque

• Instrument(s): 11c/13c Baroque lute

• Instrumentation: Solo Baroque lute

• Notation: French tablature

• Modern edition: Urtext

• Publisher: Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions

• Year of publication: 2015

• Series: Lute and Theorbo Music Collection

• Pages: 92 pp.

• Dimensions: 230 × 310 mm

• Weight: 0.320 kg

• Binding: Sewn perfect binding

• Cover: Soft cover with flaps, anti-scratch lamination, gold stamping, and spot varnish

• ISMN: 377-0-0017-8812-8

Table of Contents

Sonata 99 (A major): Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Minuet

Bourrée 44.4 (A major): Bourrée

2 pieces from Sonata 16 (A major): Vivace, Peasant Dance (Weiss)

Courante 66.3 (A major): Courante (Ct Logi)

Sonata 44 (A major): Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Bourrée, Gigue (Weiss)

Capriccio 26.8 (D major): Capriccio (Pichler)

2 pieces from Sonata 100 (D major): Allemande, Courante (Weiss)

Passacaglia 18.6 (D major): Passacaglia (by Weiss)

Fugue 48 (D major): Fugue (by Weiss)

Sonata 101 (G major): Allemande, Courante Amoroso, Peasant Dance, Gigue (Weiss)

Sonata 102 (G major): Allemande, Courante, Presto, Rondeau (Tour and Finale), Bourrée, Gigue (Weiss)

Courante 81 (G major): Courante (Weiss)

Courante 83 (G major): Gavotte (Weiss)

Sarabande 84 (E minor): Sarabande (Weiss)

Fugue 83.1 (B-flat major): Fugue (Weiss)

Courante 81.2/88.3 (C major): Courante (Weiss)

Courante 37.3 (C major): Courante (Weiss)

Sonata 104 (C major): Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Gigue (Weiss)

Press Reviews

Editions for Baroque Lute

Each volume is crafted as a work of editorial art: high-quality printing, notation faithful to original sources, dual tablature (French and Italian), and rigorous critical apparatus.

Designed for today’s lutenists, these urtext editions embody the precision and elegance inherent to the art of the lute.