Preface

Learning to play a musical instrument requires dedication, method and thoroughness, but also offers moments of playfulness, joy and passion. A few well-chosen and carefully practiced notes can fully satisfy the beginner or even the advanced musician. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the baroque lute was confined to a tight-knit circle of aristocrats and noblemen who shared an inclination for the delicate, exquisite and sublime. Today’s baroque lute has lost none of those qualities. What has, however, changed radically is the fact that nobility is no longer a matter of owning a title, but is a question of spirit and culture, and thus the fine and delicate sound of the baroque lute may be enjoyed, as well as played, by a far wider audience.

Considerations of both a technical and an aesthetic nature differentiate the practice of the baroque from that of the renaissance lute. The latter is an instrument that lends itself to solo playing as well as accompaniment, whereas the baroque lute is above all a soloist instrument. This very significant difference implies an equally different approach. Let’s take, for example, the “supreme” instrument in Western music: the human voice! A singer must first and foremost work on the quality of his/her timbre, since it is through this timbre, unique to each singer, that he/she will charm and convince the audience. The same concept applies to the baroque lute: the quality of the timbre our fingers produce when plucking the strings is the most important aspect, to be mastered from the very beginning. In this respect, be very patient and perseverant, and keep in mind that we are striving for elegance, refinement and delicacy, qualities that should help guide you in your attempts to master the sound of the baroque lute. Sound is the mirror of the soul!

Those who come to the baroque lute from the classical guitar know not only that the two instruments belong to distinct families, but that the approach to sound production for these two distant cousins is radically different. Double strings, with their greater number and lower tension, as well as a rounded body, make the baroque lute a completely different instrument. The conscientious guitarist must there- fore approach it with modesty and patience. Even those who have mastered difficult pieces on the guitar must have the humility to start from scratch, and to try to apprehend the distance separating them from the universe of the lute.

In all so-called traditional cultures, musical instruments were taught orally. Today, thanks to ground- breaking research by many musicologists, but also to great lutenists such as Hopkinson Smith, we can once again benefit from first-hand teaching of the baroque lute. Nonetheless, we encourage you to look into the historical sources available, in order to pursue the development of the “new lute tradition”, interrupted over 200 years ago.

No book or method can ever replace the role of a teacher. A teacher with a practiced ear can help a student the perceive the structure and shape of sounds he would not otherwise be capable of hearing. This capacity for discriminating sounds and structure, indispensable to the mastery of a musical instrument, can never be summed up in a few lines cast on paper. (1) That is why this method, like all those written previously and those yet to come can never fully teach you the art of becoming a musician! In this respect, the musicologist Frederick Neumann wrote in 1965 that at one time “... treatises were either unknown or neglected. Then, the enthusiasm surrounding their discovery toward the end of the [19th] century caused musicologists to overestimate their importance.

This exaggeration continues today, and is manifested in the tendency to extend the application of these treatises beyond their legitimate scope, to over-generalize isolated passages, and to regard as laws what were only rules, subject to numerous exceptions.” (2)

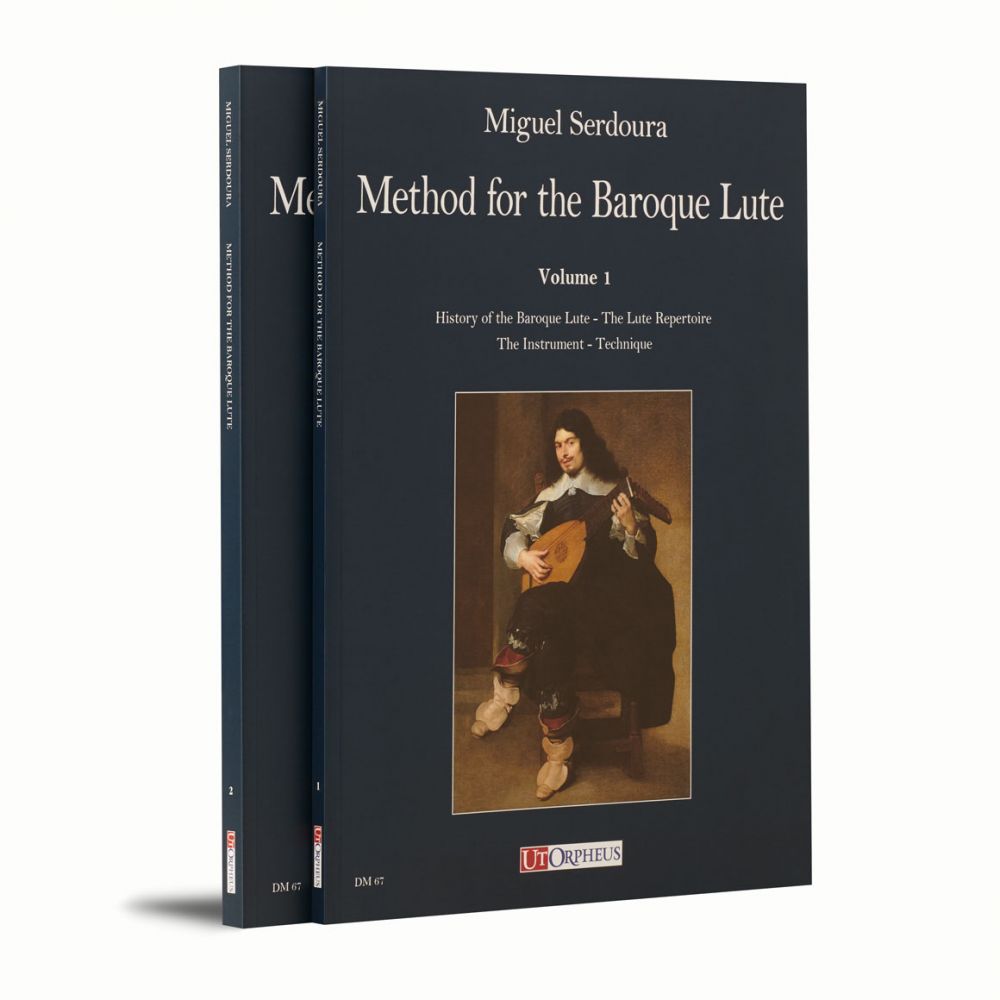

Our Method for the Baroque Lute can, however, provide you with the technical and musical foundations required for a solid and comprehensive approach to playing the baroque lute. That is indeed the purpose, and challenge, of this book: to reach out to as many lute-lovers as possible, and give them the opportunity to express themselves via the baroque lute, however advanced they may be in their musical education. Its audience includes not just those who have never played a musical instrument, but also seasoned guitarists desirous of initiation into the mysteries of the baroque lute!

Instructions

Our Method for the Baroque Lute is divided into three parts.

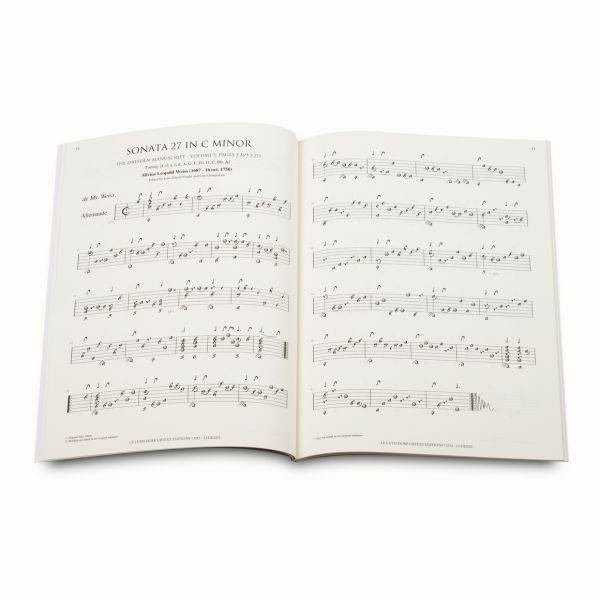

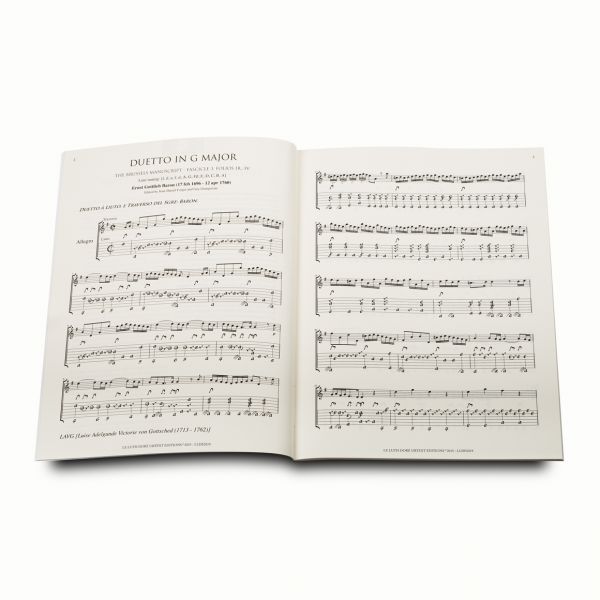

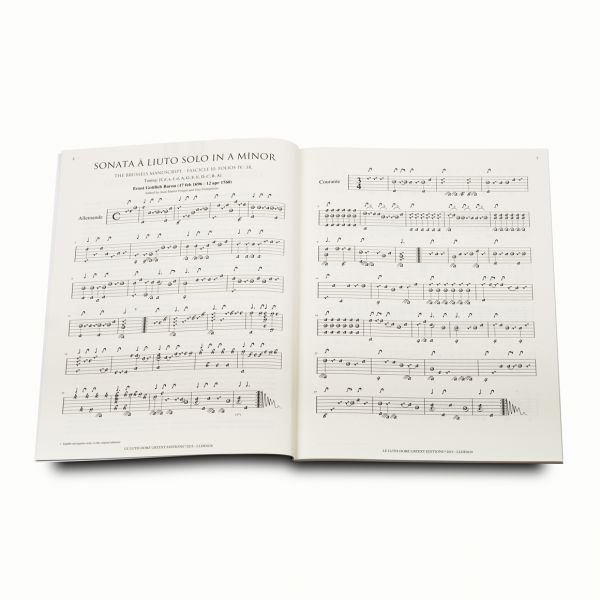

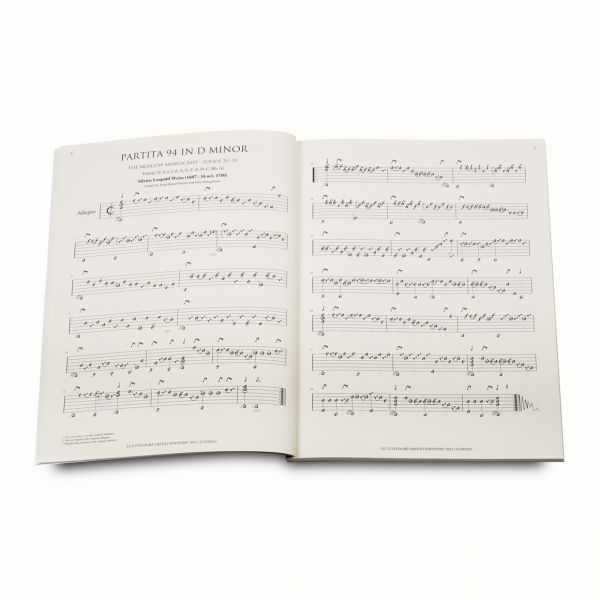

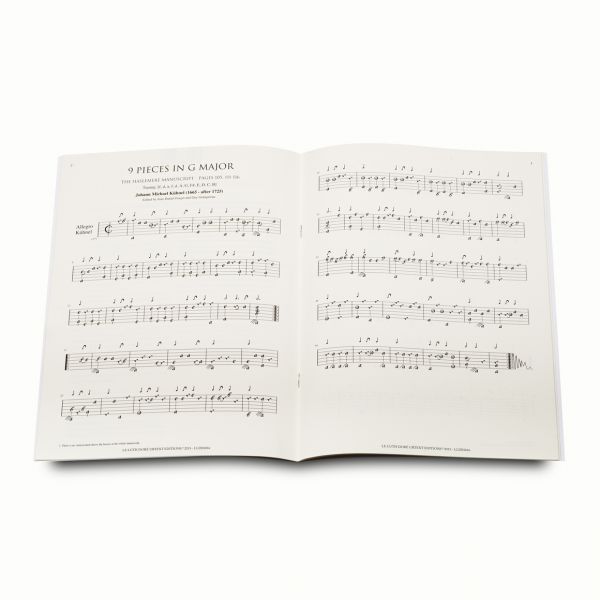

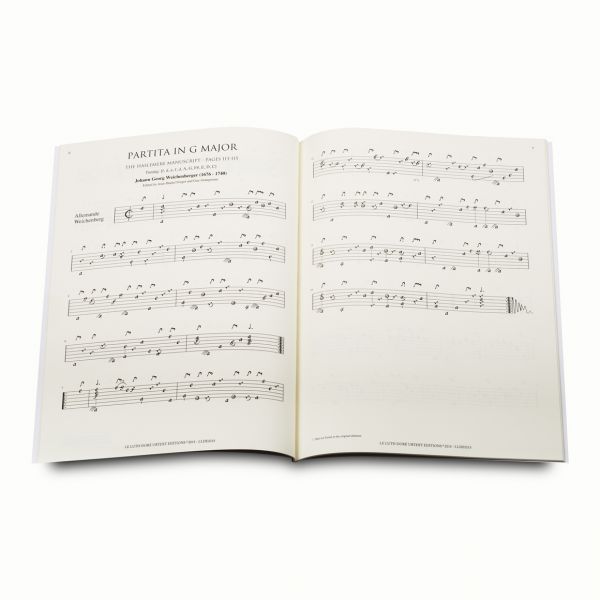

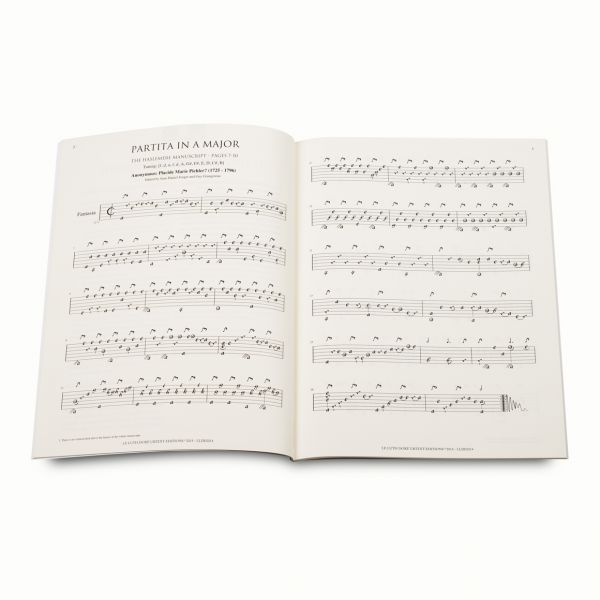

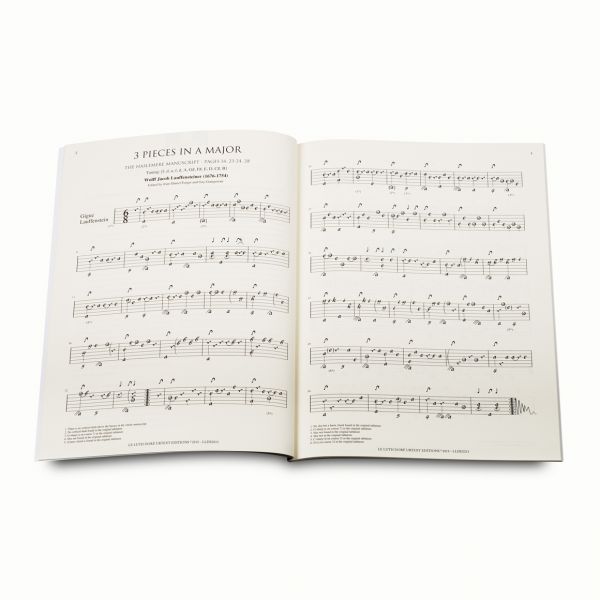

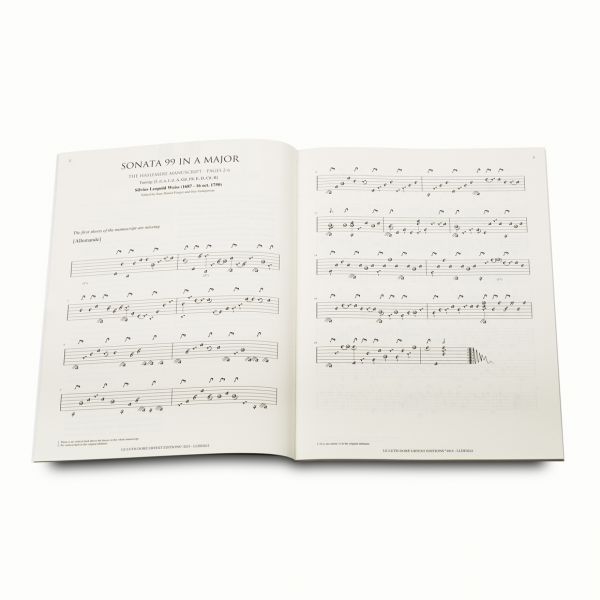

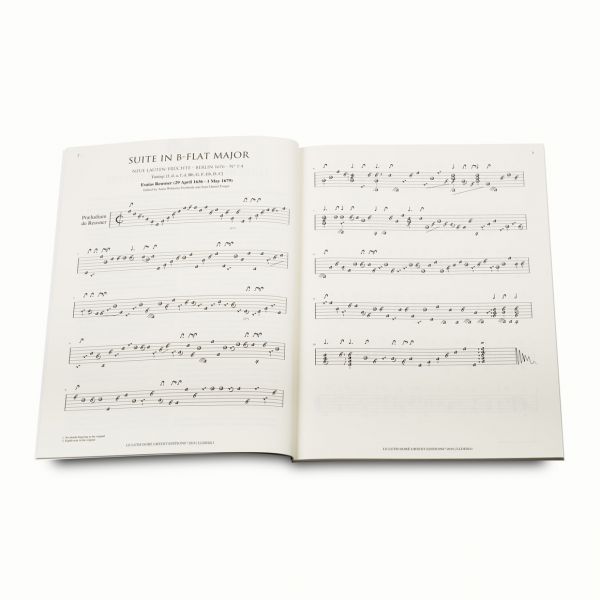

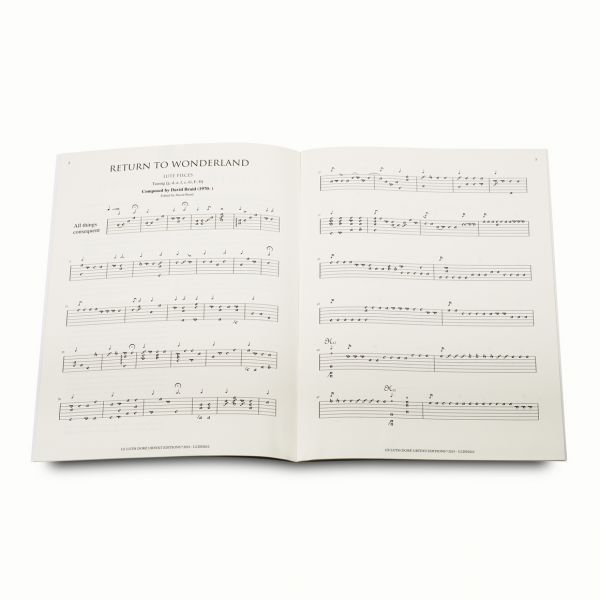

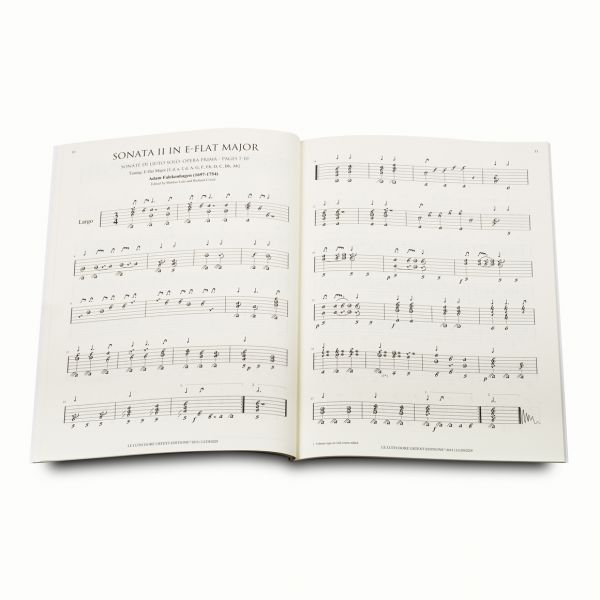

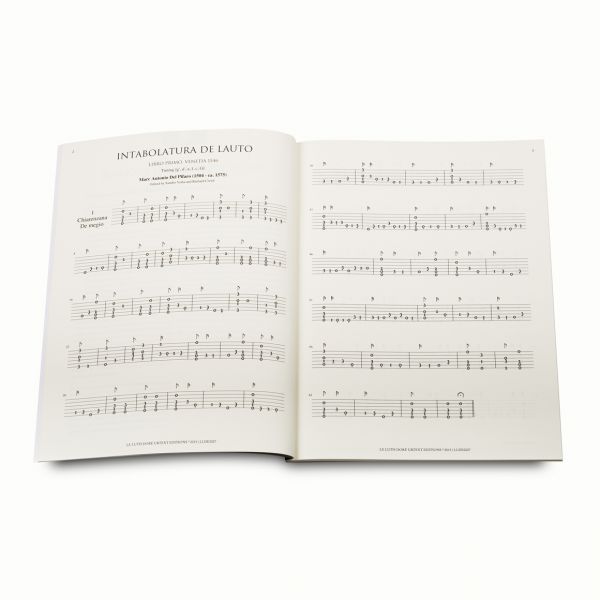

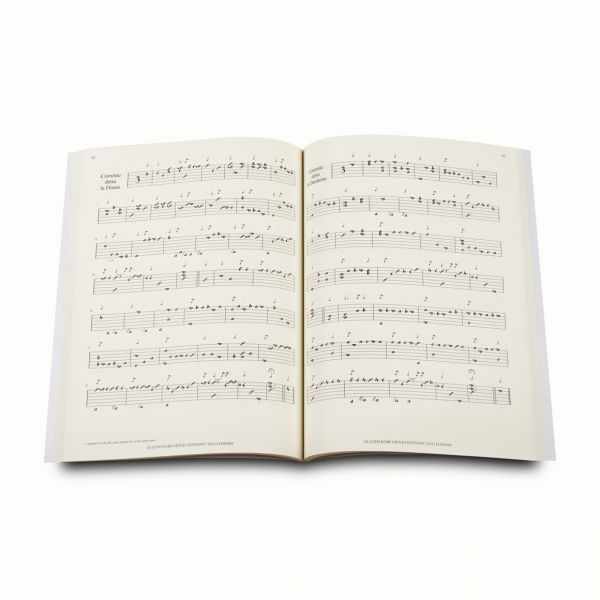

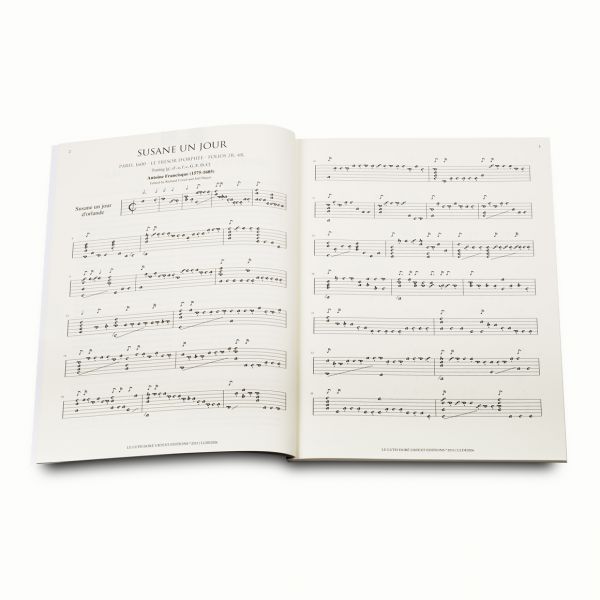

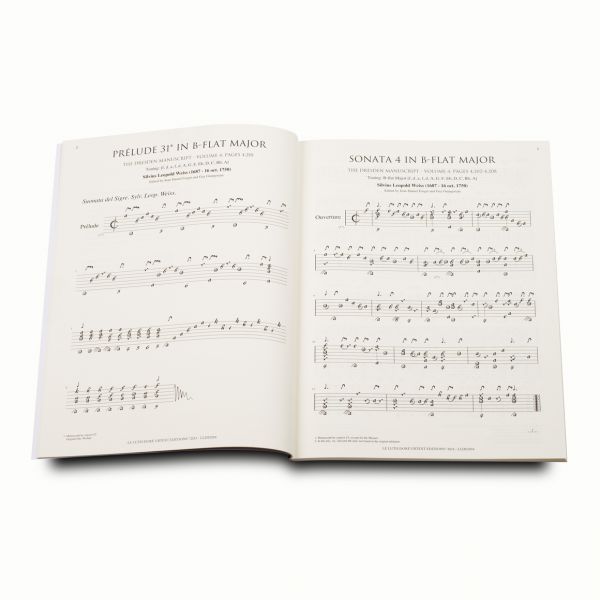

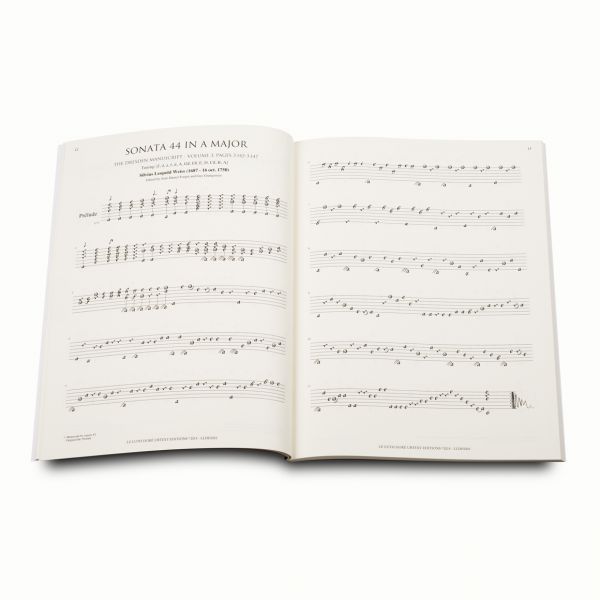

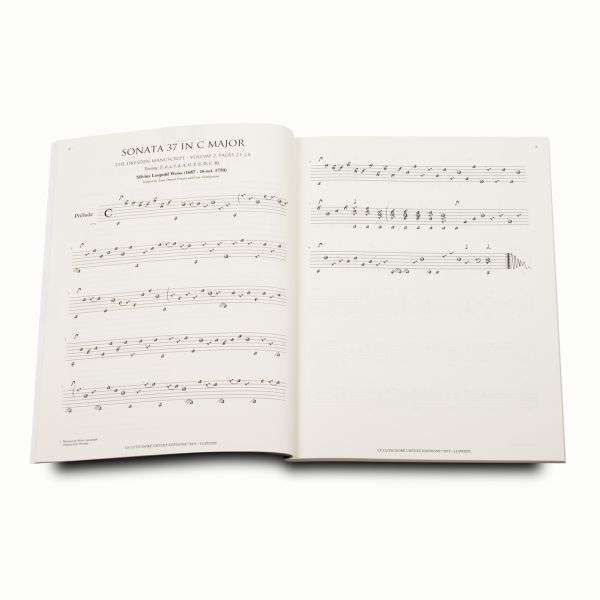

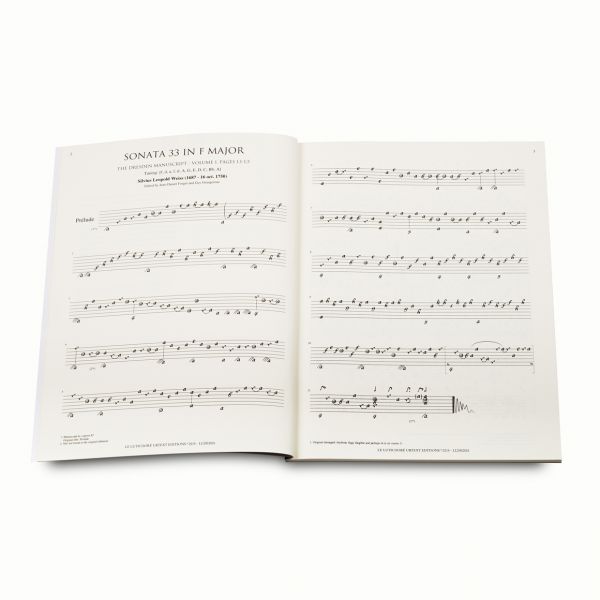

The first, mainly theoretical part, will help you better understand the way baroque lute music is to be played. We think it is necessary for the lutenist to possess some elementary knowledge of Western musical notation as well as of tablature (form of notation specific to the lute). This theoretical knowledge would not be complete if acquired by itself. We have therefore added an explicative lexicon as well biographies of most of the composers of music for the 11- and 13-course baroque lute.

The second part contains an entire chapter devoted to the study of lute technique and sound production. With a wealth of photographs and details regarding all the technical problems to be overcome, this chapter is undoubtedly the most important for achieving an understanding of the baroque lute’s acoustical properties. This is followed by 21 elementary exercises, presented in order of increasing difficulty, accompanied by several pieces. You are asked to play the melodies first, add the bass lines next, and only then begin working on the ornaments.

The third part contains 250 selected pieces for the 11- and 13-course baroque lute. The pieces are divided into three levels of difficulty: elementary, intermediate and advanced. In keeping with practice in the baroque era, the pieces are arranged by key and title. We preferred to limit ourselves to a small number of different keys, so that beginners may devote their time to the instrument, rather than to retuning it or to playing pieces far too complex for their level. There is no such thing as bad music, but sometimes there are bad musicians! Making music cannot amount to merely playing the notes, or per- forming often pointless acrobatics. A “mature” musician most often takes pleasure in playing a simple melody and enjoying the exquisite sounds of their instrument.

We hope this method can be of assistance to those who do not have access to a teacher (although we advise them to work with one on as regular a basis as possible), but also to teachers lacking sufficient material to allow their pupils to work with in a systematic way.

(1) “The development of a musical ear should consist in a gradual sharpening of the perception of the movement of sound, from a global and imprecise perception to a subtle perception of the slightest inflexions of sound.” Maurice Martenot, Principes fondamentaux d’éducation musicale et leur application.

(2) Frederick Neumann, Revue de musicologie, T. 51e, No. 1er (1965), pp. 66-92.

© 2008 Miguel Serdoura