My Store

The London Manuscript | Volume I

The London Manuscript | Volume I

SKU:LLDE0022

• Composer(s): Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687-1750)

• Title: The London Manuscript

• Year of publication: c.1717-1723

• Source: GB-Lbl Add. Ms. 30387

• Volume: I

• Scholarly edition based on original sources

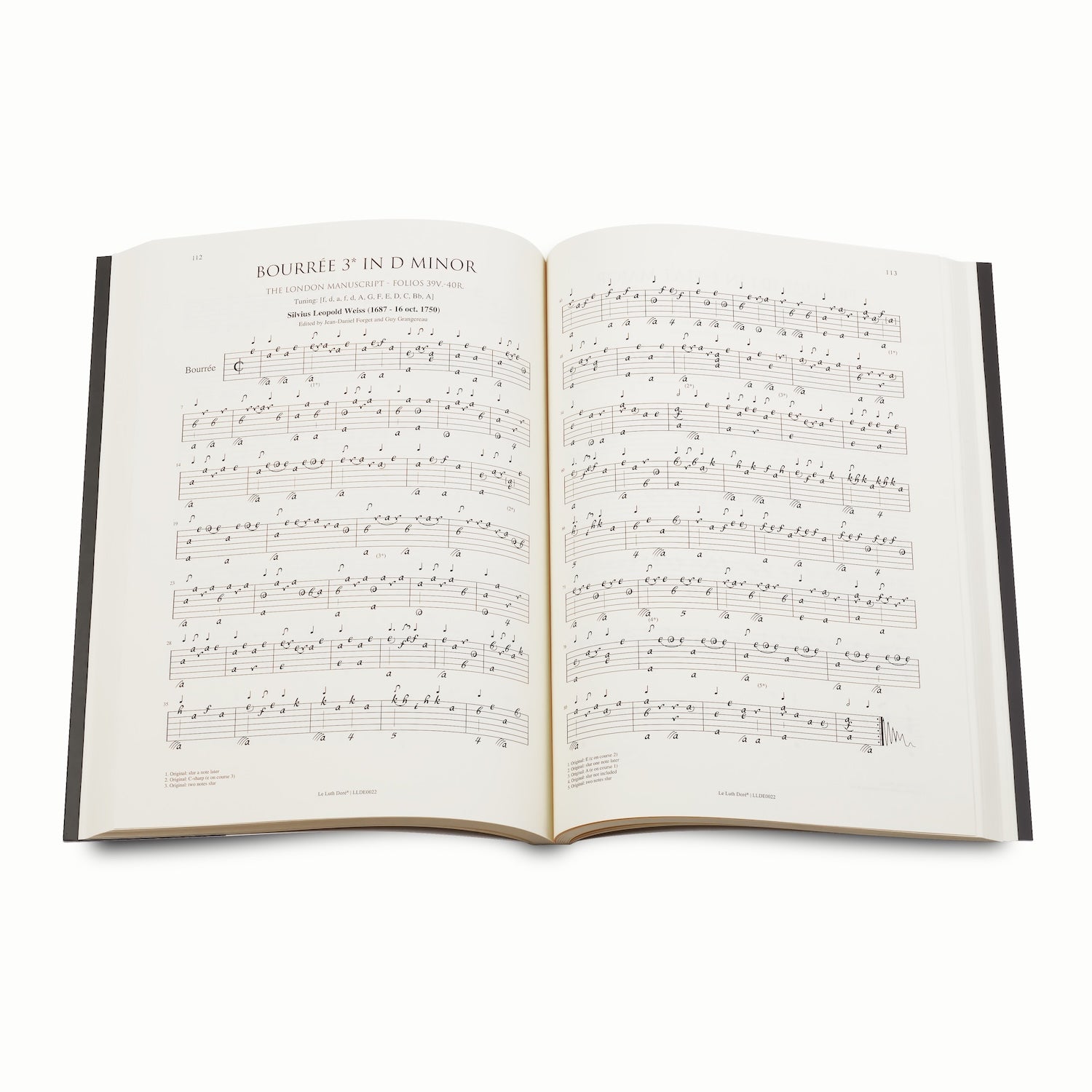

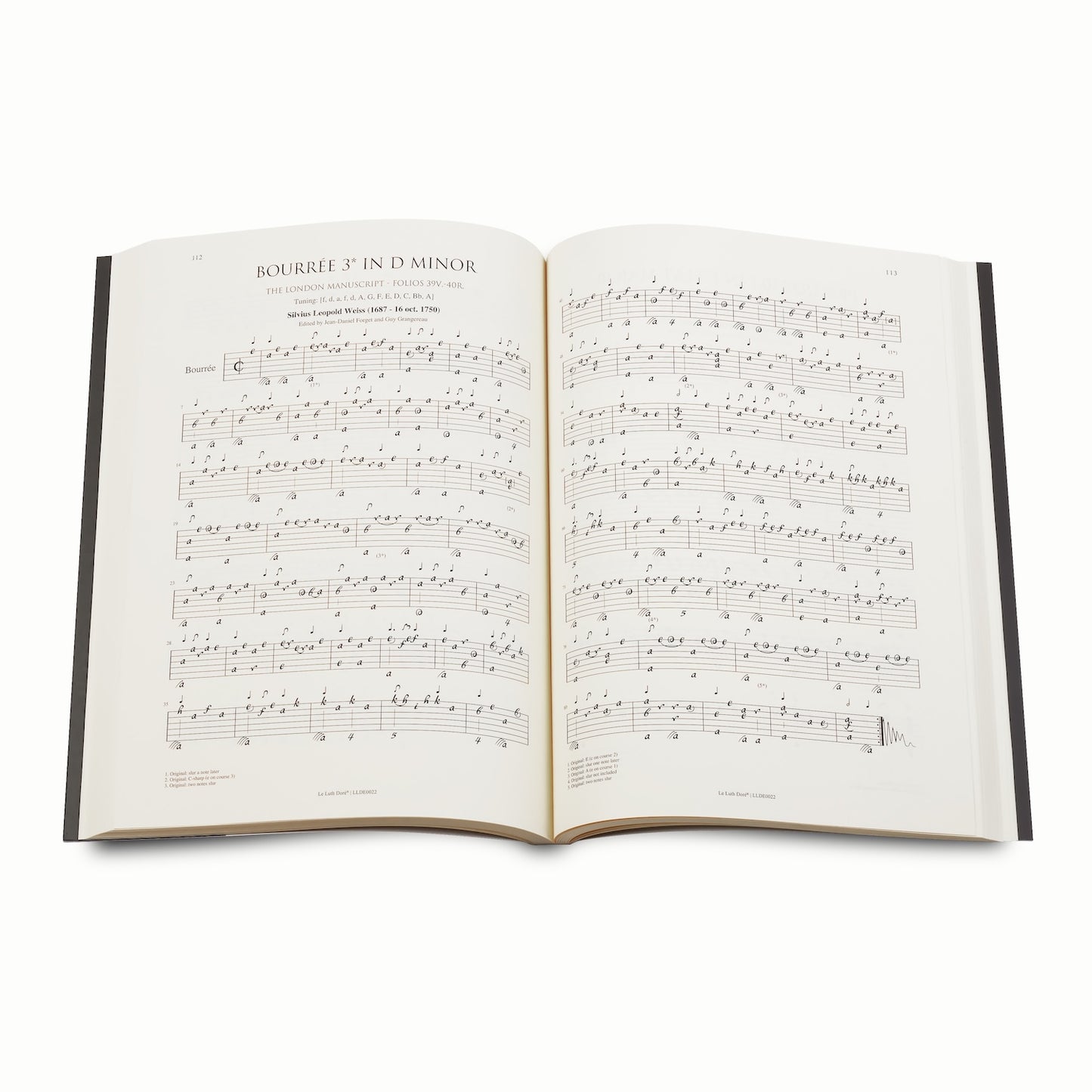

• Accurate transcriptions, historical fingering, optimal readability

• Ideal for concerts, research, or higher education

No VAT applied (Article 293 B of the French Tax Code).

Couldn't load pickup availability

Partager

Weiss in London: Between Counterpoint and Galanterie

The first volume in a collection dedicated to Silvius Leopold Weiss, this edition gathers complete sonatas and individual pieces from the London Manuscript, presented in a faithful and critical transcription.

These works illustrate the composer’s stylistic maturity, the evolution of the thirteen-course Baroque lute, and the grounding of his writing in counterpoint, galant elegance, and rhetorical expressiveness. Edition by Jean-Daniel Forget and Guy Grangereau.

Product Details

Overview

The London Manuscript by Silvius Leopold Weiss

The London Manuscript, preserved at the British Library under the shelfmark Additional MS 30387, is a 317-page collection of French tablature for the Baroque lute with 11, 12, or 13 courses. Composed primarily of works by Silvius Leopold Weiss, it contains 26 complete sonatas, as well as preludes, fugues, fantasias, tombeaux, and ensemble pieces, including three concertos for lute and transverse flute.

Annotations indicate that the manuscript was compiled in Prague between 1717 and 1723, a period during which Weiss maintained close ties with the local nobility and musicians. The presence of multiple copyists—including Weiss himself—suggests a gradual process of compilation. Research by Douglas Alton Smith and Claire Madl attributes the collection to Johann Christian Anthoni von Adlersfeld, a Prague merchant and music enthusiast.

Organized chronologically, the pieces reflect the evolution of the lute toward the galant style. From 1719 onward, they were conceived specifically for a 13-course lute. Since the 1980s, the works have been catalogued according to the WeissSW system, facilitating their identification. This manuscript remains a major source for understanding Weiss’s music and his influence on the eighteenth-century lute repertoire.

Editors

Jean-Daniel Forget – IT Specialist, Lutenist

Passionate about the Baroque repertoire, Jean-Daniel Forget is a self-taught lutenist who has been copying and distributing early music manuscripts for nearly twenty years. A professional IT specialist, he is proficient in music notation software adapted to tablature. In collaboration with Guy Grangereau, he shares tablatures on a dedicated website. He also assisted Miguel Serdoura in preparing his editions and his Baroque Lute Method.

Guy Grangereau – Guitarist, Lutenist

A professional musician, Guy Grangereau studied guitar in Paris with Turibio Santos before furthering his training at the Martenot school. He taught for twenty years and now performs on a 16-string hybrid instrument and a theorboed baroque lute. Since 2010, he has collaborated with Jean-Daniel Forget in transcribing and revising Baroque manuscripts, particularly those of Silvius Leopold Weiss.

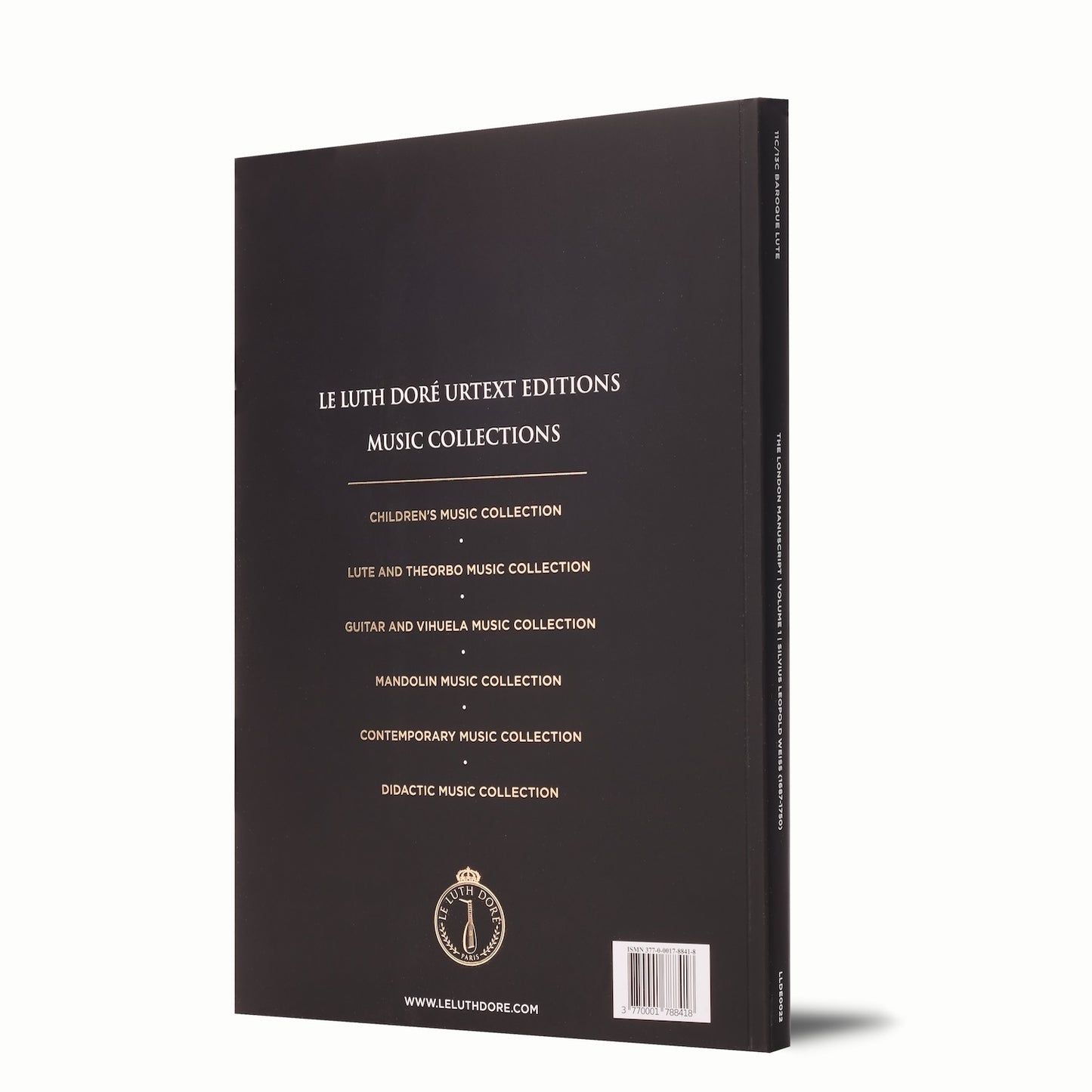

Urtext Editions

Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions

Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions offer scores faithful to historical sources, optimized for musicians and musicologists. Our editions combine careful engraving, practical layout, durable materials, and a detailed critical apparatus in multiple languages.

Each text is rigorously established note by note to ensure an authentic restitution of the works, including original fingerings and ornamentations, as well as relevant stylistic suggestions.

Prepared by experts, our editions provide clear readability and informed interpretation of the early music repertoire.

We dedicate Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions to the memory of William H. Roberts († 2024), cofounder and source of inspiration for this collection. Without his vision and unwavering support, these editions would never have come into being.

Technical Details

• Editor(s): Jean-Daniel Forget & Guy Grangereau

• Musical period: Baroque

• Instrument(s): 11c/13c Baroque lute

• Instrumentation: Solo Baroque lute

• Notation: French tablature

• Modern edition: Urtext

• Publisher: Le Luth Doré Urtext Editions

• Year of publication: 2021

• Series: Lute and Theorbo Music Collection

• Pages: 300 pp.

• Dimensions: 230 × 310 mm

• Weight: 0.924 kg

• Binding: Sewn perfect binding

• Cover: Soft cover with flaps, anti-scratch lamination, gold stamping, and spot varnish

• ISMN: 377-0-0017-8841-8

Table of Contents

Sonata 1 (F Major): Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Gigue, Minuet, Gavotte

Sonata 2 (D Major): Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Gigue, Gavotte, Double

Sonata 3 (G minor): Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Minuet 2do

Short fragment (B flat major): [Anonymous]

Sonata 4 (B flat major): Prelude, Overture (Allegro & Presto), Courante, Bourrée

Allegro 1 (G Major)* : Allegro

Courante 2 (G Major)*: Royal Current

Sonata 5 (G Major): Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Gigue

Sonata 6 (B flat major): Concert for lute & transverse flute (Weis) – Adagio, Allegro, Grave, Allegro

Sonata 7 (C minor): German, Courante, Gavotte, Sarabande, Minuet, Gigue

Sonata 8 (B flat major): Concert for lute & transverse flute (Sigismundo Weis) – Andante, Presto, Andante, Allegro

Sonata 9 (F Major): Concert for lute & transverse flute (SL Weis) – Adagio, Allegro, Amoroso, Allegro

Bourrée 3 (D minor)* : Stuffed

Prelude 10.1 (E flat major): Prelude

Sonata 10 (E flat major): Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Chaconne

Minuet 4 (G Major)* : [Anonymous piece]

Sonata 11 (D minor): German, Courante, Gavotte, Sarabande, Minuet, Gigue

Sonata 12 (A Major): Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Chaconne, Gigue

Sonata 13 (D minor): Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Bourrée, Minuet

Largo 5 (D minor)* : Long

Fugue 6 (C Major)* : Fugue

Sonata 14 (G minor): Adagio, Gavotte, Sarabande, Minuet, Bourrée, Chaconne

Fugue 7 (D minor)* : Fugue

German 8 (A minor)* :The Unhappy Lover

Fantasy 9 (C minor)* : Fantasy

Minuet 10 (B flat major)* : [Anonymous piece]

Sonata 15 (B flat major):Mons Complaint: Weis– German, Common, Peasant, Sarabande, Minuet, Jig

Sonata 16 (A Major): German, Echo Air, Peasant, Sarabande, Minuet, Pastourelle

Sonata 17 (C Major): German, Common, Bourrée, Sarabande, Minuet, Peasant

Addendum

Fantasia 11.7 (D minor): Fantasia (Dresden Ms)

Prelude 12.8 (A Major): Prelude (Dresden Ms)

Bourrée 13.4 (D minor): Stuffed (Moscow Ms)

Press Reviews

Editions for Baroque Lute

Each volume is crafted as a work of editorial art: high-quality printing, notation faithful to original sources, dual tablature (French and Italian), and rigorous critical apparatus.

Designed for today’s lutenists, these urtext editions embody the precision and elegance inherent to the art of the lute.